GIOVANNI DIFFIDENTI Photojournalist

The Legacy of the Perfect Soldier

Landmine Survivors

17

The legacy of the perfect soldier

How does it feel when your foot activates a mine? What is it like when you lose a part of your body? What does it mean to live your life disabled? These are some of the questions that I keep asking myself. I have asked and I continue to ask the same questions to different people in different countries since the perfect soldier, or rather its victims, entered into my life.

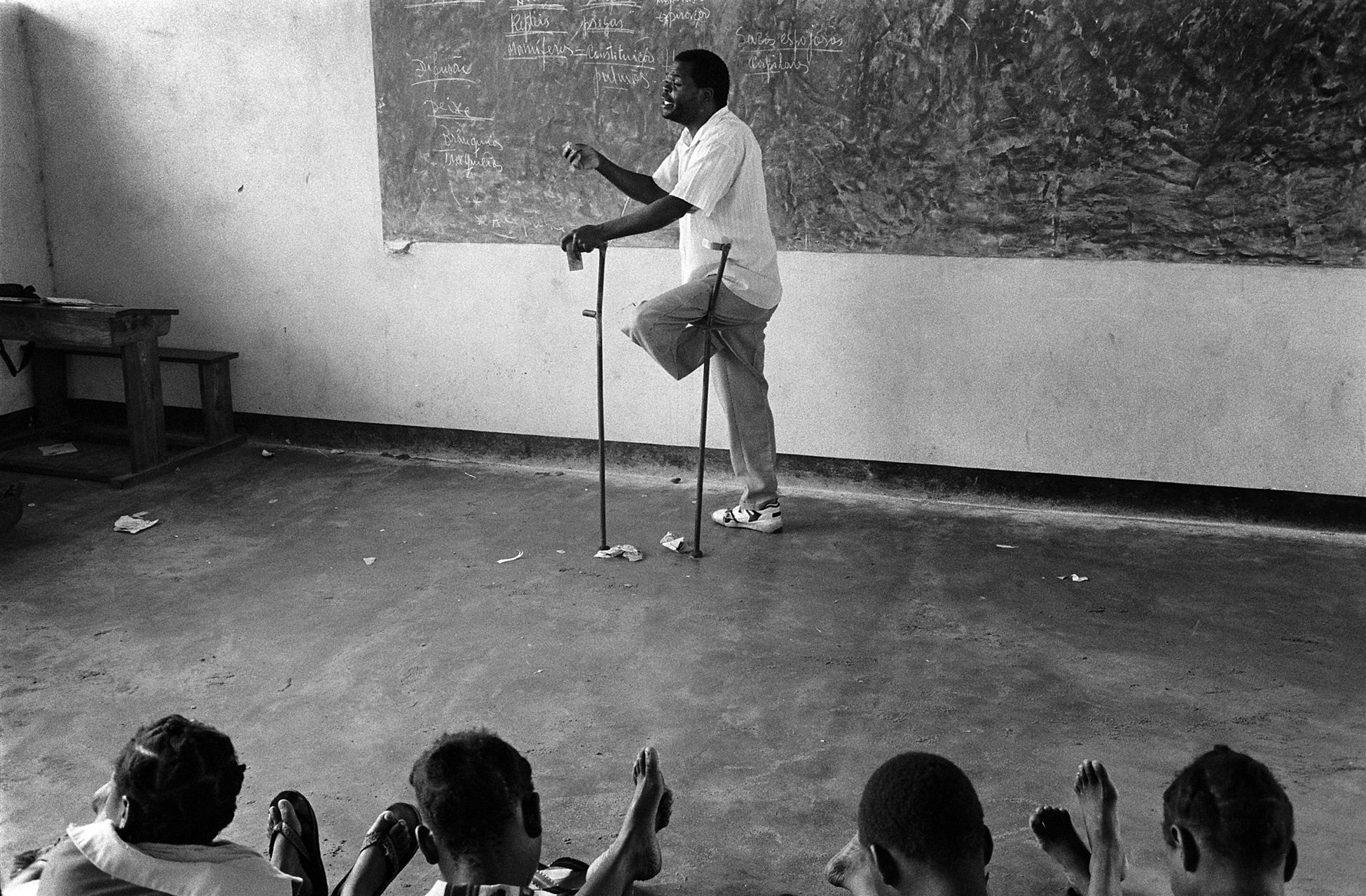

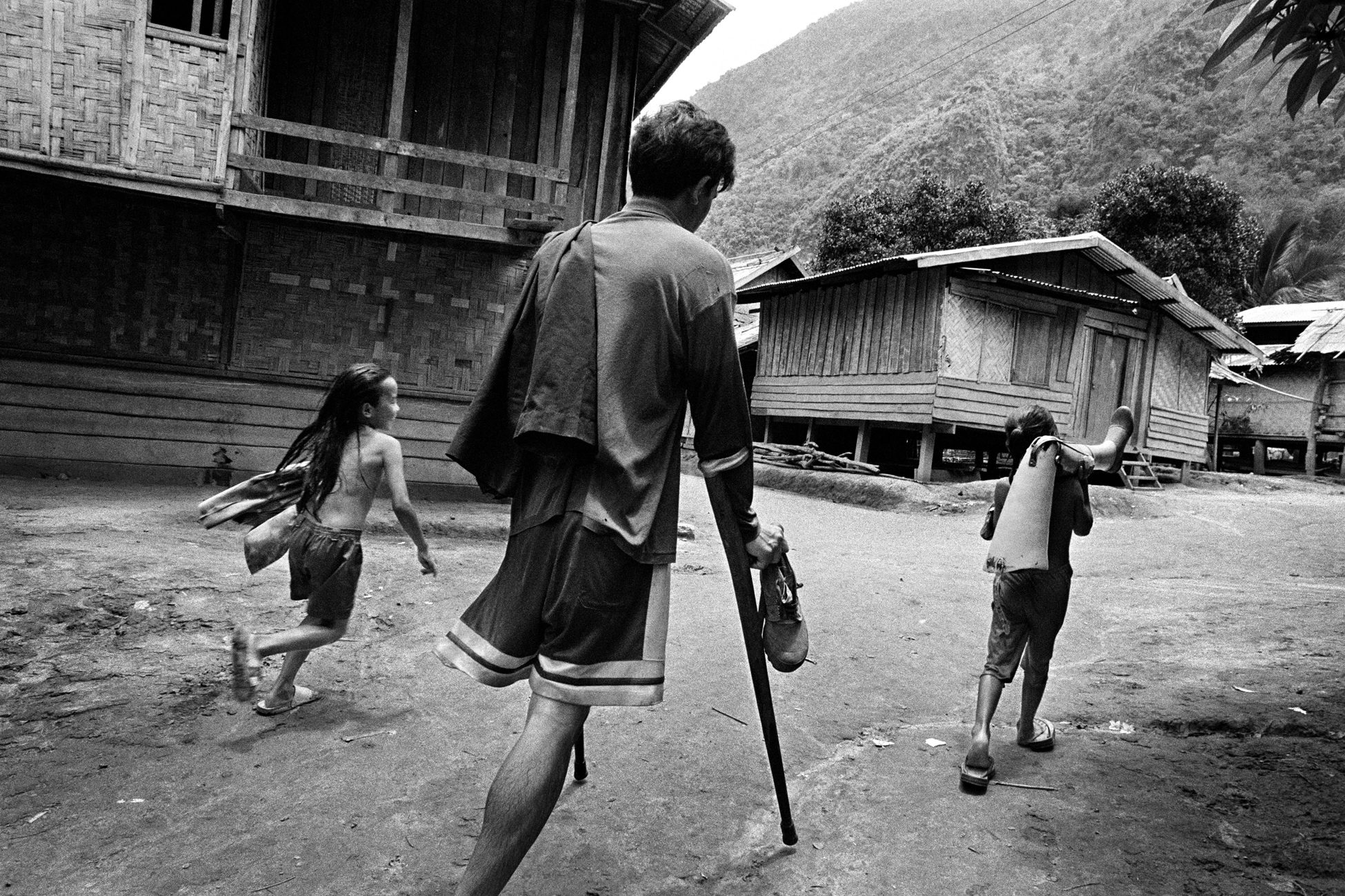

I started to document this reality in 1992, in Cambodia, in orthopaedic centres and hospital camps. I realised that the more time I spent with these people, the more my interest grew. I wanted to understand how they managed to live in their homes and in their world and how they managed to live everyday life without a leg or an arm, or even blind.

On 22nd March 1994, at half past four in the afternoon an incident occurred near an access road of the jungle. The road had been built by soldiers with the aim of surrounding the enemy. A passing tank activated a mine, causing a powerful explosion that killed two soldiers and injured six. A few minutes before this the commander of the men had ordered me to get into the truck that was following the tank, where I had been sitting all day. He told me I could consider myself lucky.

Since then, my journey has led me into countries where beauty and danger coexist in an inexplicable contrast. Throughout my journey I have met entire communities that live in the constant fear of treading on a mine. Leaving Cambodia, I found myself in Mozambique, Angola, Afghanistan, Laos, Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras, United Staes, Sudan, Egypt, Colombia, Iraq and finally Libya.

The aim of all these years has been to talk about hopes: very individual and diverse hopes. It has also been to highlight the lives of people, very different from each other but united by a common factor: the interruption of their journey through life caused by a cursed mine. They all have their own story to tell, and a reason for being exposed to a mine at that moment. A mine that was to scar them for life, both in their body and their spirit.

Waking up in the middle of the night to go to the bathroom… forgetting you have a missing leg… falling over… in the morning, instead of putting on your shoes, inserting your prosthesis… And all of this if you are lucky enough to have at least one healthy leg. For many, the day passes near a set of traffic lights asking passers-by for spare change in order to buy food, or annihilating their minds with alcohol or drugs. But there are others who resist owing to their dignity. Those who manage to live as they did before the accident occurred. And there are even some who have found ways to take advantage of their situation. The Croatian, Vjekoslave, became a national javelin champion after losing a leg. The Cambodian, Tun Cannarith, was chosen by the IBCL to receive the Nobel peace prize. But these are exceptional cases among masses of people in despair.

They didn’t choose to live this way – somebody else chose for them. Somebody sitting comfortably behind a nice desk, wearing elegant clothes, and driving around in a flashy sports car. Someone with beautiful children still unmarred, who chose to resolve a conflict through the production of mines.

Walking through the countryside in my own country – Italy – I can’t help from asking the farmers if the area contains mines, and I sometimes avoid contact with objects I see on the ground in fear of them exploding.

Constantly seeing mutilated people has made me notice the physical disabilities of people I see in the streets, and I ask myself what happened to them. Why is this man blind or without a leg? Does he feel lucky to be alive, like many of the people I have interviewed? Or is he desperate, like so many who live their lives in terrible conditions, and whose only hope is death?

I feel the need to share this story with the rest of the world. I hope my work succeeds in conveying to people’s conscience at least a part of my experience, as today there are still too many people who become the prey of these weapons. And there are too many people who think it is impossible to change the way things are. My desire is for people to abandon their feeling of helplessness by becoming aware of these atrocities, until the entire world plays an active part in making a change.

Giovanni Diffidenti

Commenti recenti